By Alex N. Carlson

Some years ago, while I was still living in Sendai, my cousin came to visit. It was autumn, the leaves had begun to turn brilliant shades of red and gold, and the surrounding countryside beckoned. Over dinner one evening with the grandparents of a close friend, we mentioned our interest in escaping the city. Did either of them, as lifelong locals, have any recommendations? “There’s a place I think you two should see,” replied the grandfather. “Mount Fubo—it’s a bit far, but they’ve built a fine monument there.” A monument? “For the American pilots. You know, the ones that crashed there during the war.”

Never before had three of the massive bombers crashed, in short succession, into the exact same mountain.

The next morning, packed into the back of the grandfather’s car, I began to wonder: what had those downed Americans been doing in rural Miyagi? Rising jagged and steep above the nearby town of Shichikashuku, the 1,705-meter tall Mount Fubo is located at the southern tip of the Zao Renpo mountain range, some three hundred kilometers north of Tokyo. Had their goal actually been Sendai and not the nation’s capital? This seemed the logical answer.

As I would later discover, the B-29 Superfortresses that began striking the Japanese mainland in late 1944 would not reach Sendai until July 10, 1945, exactly four months after the incident at Mount Fubo1. The American airmen who met their untimely end in the early morning hours of March 10, 1945, had, in all likelihood, been sent to Japan as part of Operation Meetinghouse, the large-scale firebombing of Tokyo that took place on March 9 and 10, 1945—air raids which took some 100,000 lives and left as many as one million people homeless2. Why these men were so far off course and what happened in the moments before their planes smashed into Mount Fubo are questions that invite speculation even as their answers remain frustratingly elusive.

What can we state with certainty? To begin with, a total of thirty-four Americans lost their lives. These men, ranging in age from nineteen to twenty-nine, formed the crews of three separate B-29s: an unnamed bomber from the 498th Bombardment Group (BG) piloted by 2nd Lt. Hubert L. Kordsmeier; Cherry the Horizontal Cat, a bomber from the 29th BG piloted by 1st Lt. Firman E. Wyatt; and another unnamed bomber from the 19th BG piloted by Capt. Samuel M. Carr3. While this information helps us determine where and when these men began their journeys, it does little to clear the fog from what followed. Though there had been numerous instances of B-29s straying from their flight paths; never before had three of the massive bombers crashed, in short succession, into the exact same mountain4.

Some of the mystery surrounding the accidents may be cleared up by taking into account an early-1945 change to America’s aerial strategy in the Pacific. On January 20, Gen. Curtis E. LeMay took charge of the 21st Bomber Command, the unit tasked with carrying out B-29 raids against the Japanese home islands5. Seeking to maximize his fleet’s destructive potential, LeMay called for greater use of incendiary bombs coupled with a lowering of the altitude at which crews dropped their payloads. As it happened, these tactics were first employed during Operation Meetinghouse6.

Late on March 9, as upwards of three hundred B-29s barreled through the darkness en route to the Japanese capital, they were flying at heights between approximately 1,500 and 1,800 meters (7,500–9,500 meters had been the approximate standard before). Not only did this expose them to anti-aircraft fire, it turned the landscape itself into an enemy. A quote from 1st Lt. George E. Albritton, a navigator who participated in the attacks, gives some indication of the dangers that were involved: “. . . we were in a terrible storm and the radar would not function . . . We flew on for some time in the storm and tried flying as wingman on another B-29 . . . After [calculating our position using the North Star], I notified the airplane commander that we were 60 miles [97 kilometers] north of Tokyo, and that we had to be northeast for if we were northwest, we would have flown into Mount Fuji [emphasis added] . . ."7 Could it have been that the three stranded bombers had faced a similar situation later that same night?

Not only did this expose them to anti-aircraft fire, it turned the landscape itself into an enemy.

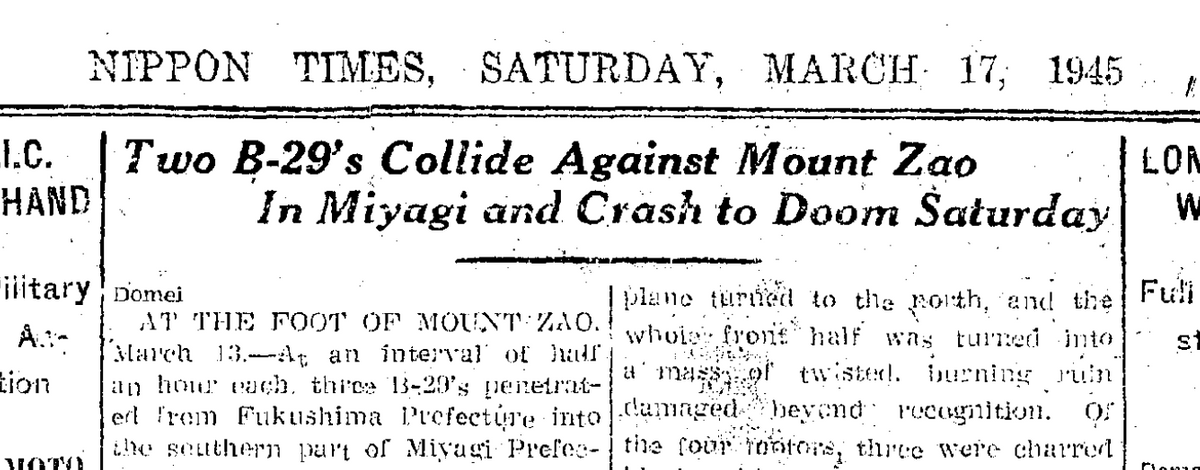

Contemporaneous newspaper accounts do not offer much insight into what the weather was like, noting only that Mount Fubo was covered in snow. Ascertaining the timing of the incident is likewise difficult. The most precise timeline is given by the English-language Nippon Times, which on March 17, 1945, ran an article stating that “At an interval of half an hour each, three B-29’s penetrated from Fukushima Prefecture into the southern part of Miyagi Prefecture about 2 a.m. Saturday [March 10] . . .” The article goes on to say, however, that of the three bombers, only two crashed into Mount Fubo. Clearly, nothing about the incident was readily apparent.

Image courtesy of the Nippon Times (日本タイムズ)

Theories aside, there is in fact something of an “official” history, recorded on the largest of the four steles that serve as the centerpieces of the Fubo Memorial Park. According to this version, a fierce blizzard was sweeping across southern Miyagi the night of March 10 and intervals of several hours separated the planes’ appearances. This would mean that the last crash occurred nearly twenty-four hours later than the time suggested by other sources, a discrepancy difficult to overlook. At the same time, to focus exclusively on historiographical inconsistencies risks minimizing the forward-looking purpose for which the park was built.

The first effort to commemorate the incident came in 1959 with the formation of a committee—the Fubo no Kai—in nearby Shiroishi City. Chaired by City Assemblyman Shoji Taketaro, the group carried out a nationwide donation drive in order to realize their goal of constructing a monument to the American airmen atop Mount Fubo. The group managed to collect over one million yen, and on September 23, 1961, the Fubo Stele was unveiled during a mountaintop ceremony.

Then, in 2014, with the seventieth anniversary of the end of Asia-Pacific War quickly approaching, a group of local leaders launched an effort to construct a more expansive memorial below the mountain. The fruits of their labor were revealed on August 2, 2015, in a ceremony attended by some five hundred people, including representatives of US Forces Japan and the American government. Sitting on roughly thirty acres of land overlooking nearby Lake Choro, the Fubo Memorial Park includes a replica of the original 1961 stele (which intrepid climbers may still visit) and thirty-four markers—each shaded by a flowering dogwood tree—listing the names of the American airman whose lives were cut short at Mount Fubo.

As I strolled through the park that November morning, I was first struck by how impossible the whole thing seemed. Compatriots though they may have been, those thirty-four Americans had come as an invading force to cause death and destruction. It was then that I passed the stele displaying a message from then US Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy: “May each of us ask what we can do to work for peace and goodwill.” I turned to see my friend’s grandfather walking on ahead, and his enthusiasm for the park visit suddenly made sense. I am immensely grateful for his invitation.

Endnotes

1. Mark Selden, “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq,” Japan Focus, 7.

2. David Fedman & Cary Karacas, “A Cartographic Fade to Black: Mapping the Destruction of Urban Japan During World War II,” Journal of Historical Geography, 319–320.

3. These are all listed on the monument at Fubosan Peace Park. Also, in Robert F. Dorr, Mission to Tokyo: The American Airmen Who Took the War to the Heart of Japan, 191–195.

4. Dorr, 163–164.

5. Graham M. Simons, B-29 Superfortress: Giant Bomber of World War Two and Korea, 91–97.

6. Ibid, 99–102.

7. Dorr, 140–141.

Fubo Memorial Park・不忘平和記念公園

Language: Signs within the memorial park are bilingual Japanese-English

Official Facebook Page: facebook.com/財団法人-不忘平和記念公園

Address: Choro, Shichikashuku, Katta District, Miyagi 989-0508 (〒989-0508 宮城県刈田郡七ヶ宿町長老)

Access: About 80 minutes by bus from Shiroishi Station or Shiroishi-Zao Station, followed by a 5-minute walk. At Shiroishi Station (白石駅) or Shiroishi-Zao Station (白石蔵王駅), board a Shichikashuku Shiroishi Line (七ヶ宿白石線) bus bound for Shichikashuku-machi Yakuba (七ヶ宿町役場). Alight at the final stop. Transfer to a Shichikashuku Choro Line (七ヶ宿長老線) bus bound for Yokokawa・Choro (横川・長老), alight at Choro Kominkan (長老公民館) bus stop. Bus timetables here (Shichikashuku Shiroishi Line) and here (Shichikashuku Choro Line).

Mt. Fubo・不忘山

Details: town.shichikashuku.miyagi.jp

Address: Obukasawa, Shichikashuku, Katta District, Miyagi 989-0500 (〒989-0500 宮城県刈田郡七ヶ宿町大深沢)